The tragedy of Yahya Sinwar

Yahya Sinwar has reshaped the Middle East, and his legacy will echo for decades. Who was he? Why did he initiate the 7 October attacks in the manner that he did? How will he be judged?

The figure of a leader

During the 22 years he spent in an Israeli prison, Yahya Sinwar’s jailers developed a near-consistent impression of him.[1] He was “super-intelligent.” His average grade across the 15 university-level courses he took by correspondence in Hebrew, mostly in Jewish history, was 90. Interrogators, observed “cleverness, guile,” and a mind not merely academic but active and organisational.

He was charismatic, both in public and private. “He knew how to excite the masses,” had the “ability to carry crowds.” He recruited people to confront the army in Gaza, or the warders in prison: dangerous tasks, that many refuse. “But with Sinwar no one declined.”

His Israeli interrogators noted his “cruelty and hardness.” They found him “cunning and manipulative”, “psychopathic”, “brutal”, “a leader with the personality of a murderer.” They recount stories of his work as Hamas’s counter-intelligence chief for the southern Gaza strip, during which he killed, according to his own confession, four Palestinians accused of collaboration. They claim he strangled a man with a kufiyyeh in an open grave, tortured victims with boiling oil, and killed a barber on a mere rumour that he shared obscene material. Once in prison, he is alleged to have ordered the beheading of two fellow inmates whom he believed were collaborators. Those claims are uncorroborated. But, according to a transcript seen by the New Yorker, he confessed to having a cell-mate’s sister in Gaza murdered because she was having an affair.

One interrogator asked him if the freedom of 100 prisoners was worth the death of 10,000 innocents. "Even 100,000 is worth it," Sinwar replied. The retort – like several of Sinwar’s exchanges with his jailers – has a performative, exaggerated quality to it. To take it too literally would be to miss the point: defiance.

Prison is hard. But Sinwar’s determination, his defiance, never wavered. “He always spoke with head held high, aggressively, authoritatively.” He promised one interrogator:

You know that one day you will be the one under interrogation, and I will stand here as the government, as the interrogator. I will interrogate you. . . Our roles will be reversed. The world will turn upside-down for you.

One of Sinwar’s interrogators was asked if Sinwar was willing to die for his cause:

He is. Definitely. That's the difference between him and the Hamas leaders who were released in the Shalit deal, and are living decadent lives in Turkey or Qatar. They forgot their people. Sinwar is not like that. . .

Cruelty and history

Was cruelty Sinwar’s cardinal flaw? Was it that which brought ruin to Gaza?

In 1923 the health of Vladimir Illich Lenin was fast declining. The assassin’s bullet that lodged in his skull a year earlier had all but destroyed his powerful mind. But for a young David Ben Gurion, whose Zionism was always inflected with the socialism prevalent in the Polish-Jewish milieu of his youth, Lenin was the ideal leader of a movement seeking to attain and defend state power:

A man who disdains all obstacles, faithful to his goal, who knows no concessions or discounts, the extreme of extremes; who knows how to crawl on his belly in the utter depths in order to reach his goal; a man of iron will who does not spare human life and the blood of innocent children for the sake of the revolution . . . he is not afraid of rejecting today what he required yesterday, and requiring tomorrow what he rejected today; he will not be caught in the net of platitude, or in the trap of dogma; for the naked reality, the cruel truth and the reality of power relations will be before his sharp and clear eyes . . .

Ben Gurion remained faithful to this ideal, but despite the violence of the language, for the greater part of his career he realised it as much through restraint as aggression. During the Great Revolt, as the “revisionist” Zionist factions killed 250 Palestinian civilians, he held back Haganah, the militia under his direct control. During the 1940s he collaborated with the British authorities to curtail revisionist attacks on British troops and policemen.

In both cases, he used restraint to strengthen the position of the Jewish community in Palestine: an improved relationship with the British authorities, official sponsorship of Jewish militia units, control of port labour. Yet his goal, and its implications, were clear. “We must expel the Arabs and take their places,” he wrote to his son in 1937. And when the time came, in 1948, a quarter century after his meditation on Lenin, he showed that he was as ruthless as his ideal demanded.

Ben Gurion notoriously remarked shortly after Kristallnacht that he would rather have brought half the Jewish children in Germany to Israel than save them all by bringing them to England. We should take him at his word: he did not disdain Jewish life, but believed Jewish life was best preserved in the long run by a state. Sinwar’s philosophy was similar. In a message to Hamas negotiators in Doha this year, he described the dead Palestinians in Gaza as “necessary sacrifices,” comparing the Palestinian case to the Algerian independence war, in which perhaps four hundred thousand Algerians are thought to have been killed.

It is hard to take the professed revulsion of Sinwar’s Israeli interrogators seriously.[2] They must have known that their own government was responsible for many more civilian deaths than Sinwar. They ought to have known that it is wholly ordinary for national movements to execute suspected collaborators; indeed the pre-state Zionists, “permitted themselves to execute people without conclusive evidence.”

Even the South African anti-apartheid movement, whose relative moderation is often proposed as a model for the Palestinian national struggle, carried out executions of supposed collaborators. The African National Congress disavowed the most extreme version of this practice, in which the victim was restrained and a burning tire filled with petrol hung around their neck, but not the killings as such.

The case against Yahya Sinwar cannot be that he was willing to kill collaborators on flimsy evidence, nor that he was willing to accept the deaths of large numbers of his countrymen in the pursuit of liberation. Ben Gurion was just as brutal, or would have been if the circumstances had demanded: he knew that about himself, even if his latter-day admirers have been reluctant to face that fact. Founding a new state in the modern world is not a gentle business.

The case against Sinwar must be not that he was cruel, but that he lacked political judgement, and that in consequence he brought upon his people a deluge of destruction and torment without advancing their struggle. But this case is not a straight-forward one, for the power relations in which the Palestinians are embedded are treacherous, and a clear path hard to discern.

Sinwar left prison in October 2011 and was elected Gaza leader of Hamas in February 2017. He prepared for war: the Al-Qassam brigades continued to develop the home-grown military industry, which has been the foundation of the organisation’s limited but real ability to damage Israel’s army over the past year. But he also sought compromise.

Compromise and politics

Throughout his tenure as leader, Yahya Sinwar sought rapprochement with Fatah, and the reunification of the Palestinian democratic polity, which had been split in two since 2007.[3] He concluded three agreements with Fatah before October last year, none of which came to anything. There were several reasons: President Mahmoud Abbas was unwilling to call elections that he was likely to lose; both the U.S. and Israel threatened to collapse the Palestinian Authority if it included Hamas; Hamas was willing to give up civil control of Gaza, but not to disarm.[4]

Sinwar also backed popular, unarmed resistance. The protests at the Gaza border fence known as the Great March of Return were initiated by independent activists. They were not wholly non-violent: there was some stone throwing, and a few flammable projectiles, but they were overwhelmingly civilian in character. Israel responded to the demonstrations with live fire, killing 223 Palestinians and wounding more than 9,000, often by deliberate maiming. No Israeli civilians were ever in harm’s way. Israel’s response was widely condemned by international rights organisations, but the U.S. blocked two critical statements at the U.N. Security Council. For Israel, there were no negative repercussions.

Sinwar also reached out to the Israeli public and the international community. A 2018 interview published in the Israeli newspaper Yediot Aharonot conveys Sinwar’s most sympathetic presentation. He offered Israel no more than a temporary truce; and asked in exchange for a cessation of the siege on Gaza. But throughout, his interest in a new dispensation seems sincere.

I am saying that I don't want war anymore. I want the end of the siege. You walk to the beach at sunset, and you see all these teenagers on the shore chatting and wondering what the world looks like across the sea. What life looks like. It [breaks me to see it]. And [it] should break everybody. I want them free.[5]

Soon after his return to Gaza he had married. The first words of his eldest son were “father,” “mother”, and “drone.” Sinwar was now a parent and a statesman. The armed struggle until total victory he had envisioned in his 2004 novel The Thorn and the Carnation, might suddenly have held less allure. Or was it just an act?

The interviewer pressed him, aware of Israel’s allegation that Hamas’s refusal to renounce the Palestinian claim to the whole of Palestine is a sign that Hamas would use any alleviation of the siege as an opportunity to arm itself for an inevitable attack on Israel. He held out the possibility that material relief would be the foundation of a continuing peace: “if we start to see a difference, we can go on.” He asked,

for once, can we imagine instead what happens if it works? Because it might be a powerful motivation for doing our best to make it work, no? . . . Let's give our kids the life we never had. And they will be better than us. With a different life, they will build a different future.

That isn’t a bankable offer of a permanent peace. But it is a credible description of a process by which one could come about, if Israel and its international allies were interested in that goal. Sinwar also talks sympathetically about his own political evolution, from the time he was imprisoned:

. . . we changed as you changed. As everybody changed. It was 1988, and as I told you, we still had the Cold War. And the world was much more ideological than today. Much more black and white, friends and enemies. And our world, too, was a bit like that. Then, over time, you learn that you can find friends, and enemies, where you wouldn't expect.

In March 2021, Sinwar was re-elected leader of Hamas in Gaza. According to a recent allegation, the vote was rigged for Sinwar by members of the organisation’s military wing, who intimidated polling station chiefs.[6] But either way, it was close, and Sinwar was under pressure: for four years he had tried, as he saw it, rapprochement with Fatah, outreach to Israelis, and unarmed, mass struggle. It had got him, and Gaza, nowhere; and now his leadership was in doubt. Conditions in Gaza had continued to decline; the popular pressure for Hamas to alleviate the crushing poverty and frequent power cuts was rising. He needed a new approach.

And then there came the Unity Intifada. In May 2021, protests against the eviction of Palestinian families from Sheikh Jarrah, East Jerusalem were met with violence from Israeli settlers and police. Sinwar gave Israel an ultimatum: to withdraw its forces from Sheikh Jarrah and the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound by 6pm on 10 May. His deadline came and went; Hamas and Islamic Jihad fired rockets into Israel. Israel, of course, hit back: the one week exchange of fire killed around 14 civilians in Israel, and more than 250 in Gaza. But for Hamas, and for Sinwar personally, it was a victory. A photograph of him sitting, smiling, on an armchair amidst the rubble of his destroyed home, went viral; an eery presage of his last stand, more than three years later.

Now, as he walked the streets of Gaza he found that he was popular: for the first time, he seemed to matter not just to Hamas, but to Palestinians as a whole. And while President Biden described the ceasefire as “mutual, unconditional”, an Egyptian official said that tensions in Jerusalem would “be addressed.” Sinwar seems to have intuited what has since been proven: that it was the intercession of President Joe Biden that brought about that compromise. “We forced ourselves on the U.S. administration and made it change its priorities so that the Palestinian issue would be the world’s top priority,” Sinwar said a few days later.[7]

In retrospect, those two months, from his hard-fought re-election in March 2021 to the exchange of fire with Israel in May, were the axis on which Sinwar’s strategy turned. The election showed him that he needed a new course, and the Unity Intifada indicated what that new course might be. The episode had been significant for several reasons: it was the first time Gaza had initiated a conflict with Israel, rather than the reverse, and the first time that it had fought explicitly for general Palestinian interests: Al-Aqsa and East Jerusalem. It had also managed to draw participation from beyond Palestine. Hezbollah and Palestinian groups based in Lebanon and Syria had sent a small number of rockets over the border. In military terms, this was a mere gesture, but in the febrile climate of those days it gave rise to a notion, which gradually evolved into a strategic concept: “the unity of the arenas.”[8] The idea was that partners to the “axis of resistance,” which includes Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran and others, should fight together in future.

That summer, Israel’s military intelligence changed its assessment of Sinwar. They had thought him pragmatic, cautious, and open to compromise; now they found him ideological, maximalist, and messianic. A security source told Ha’aretz that Sinwar believed he had been touched by God; instructed to defend Al-Aqsa and lead the Arabs. Perhaps it was easier to believe that Sinwar was a mere zealot than that he was a politician, whose posture responded to the sorts of opportunities and pressures, both domestic and external, that also shape Israel’s behaviour.

In a speech shortly after the exchange of fire, Sinwar again appealed to “the civilised and free world”, and to President Joe Biden personally, to “force the occupation to comply with international law and international resolutions.” Still, he offered Israel no more than “a long truce for four, five years or more.” In all likelihood, no formal concession by a leader of Hamas would have been enough to persuade Joe Biden, who was for decades one of Israel’s least-critical congressional supporters. But a five-year truce was far-short of what would have been needed to gain the sort of purchase in Washington D.C. that he wanted, and needed, even from a more sympathetic figure. It was less than what he had seemed to offer the previous year; a truce lasting a generation. Perhaps, if the international community had been willing to offer more, Sinwar would have, too.

By late April 2022, Sinwar’s language had become more violent, even apocalyptic. Violations of the Al-Aqsa mosque had always moved Sinwar to his harshest words and boldest action.[9] Now, a three-week series of clashes around the compound had culminated in an Israeli police raid that left twenty two Palestinians in hospital.[10] The next day, Sinwar warned that further violations of the Al-Aqsa Mosque would lead to a “regional religious war.”

“From satellites, the entire region should be seen engulfed in raging fire,” he thundered. He spoke directly to Palestinians in Israel, exhorting them to be ready to attack individual Israelis should such a war break out: “whoever has a gun should prepare it and whoever does not have a gun, should prepare his cleaver, axe, or knife.” He claimed that such attacks had “proven extremely successful.” The “unity of the arenas” idea was at the forefront:

soon we will begin coordinating with the Jerusalem axis [the “axis of resistance”], in order to start the maritime navigation route to the Gaza strip. We will completely shatter the siege, God willing. The discussions and consultations about this are well underway. We will [sail] out of Gaza, return to it, and we will import and export goods and whoever is not happy about this – we will do this whether they like it or not.[11]

He sounds like a man with his back against the wall: the extremity of his language and the wildness of his promises are a world away from his reflective, hopeful interview in May 2018.[12]

Throughout Gaza, popular discontent was building. Protests against the state of the economy, and the rampant power cuts, drew thousands in the summer of 2023. Some demonstrators burned Hamas flags, and raised a chant from the revolution in Egypt a dozen years earlier, this time directed against Hamas, and against Sinwar: “the people want the fall of the regime.”

After us, the flood

There are two fundamental criticisms of Sinwar; one strategic; the other, political.

The strategic criticism is that Al-Aqsa Flood has brought about the destruction of Gaza and the killing of one in every 50 of its inhabitants, but not advanced Palestinian interests. Yezid Sayigh, the celebrated historian of the Palestinian armed struggle, has said that the attacks set the Palestinian cause back thirty years. It seems possible. At the time of writing, there is a real risk that northern Gaza will be ethnically cleansed, and the land annexed by Israel. It may prove to be a permanent defeat.

What was the alternative? Sinwar had tried mass protests. He had tried, as he saw it, to open the door to a new round of negotiations, and to reestablish Palestinian electoral democracy. What was left?

One option was an armed attack on solely military targets. Shortly after 7 October last year, Professor Lawrence Freedman argued that such an attack would have won the “grudging admiration” of world opinion, embarrassed and isolated the Israeli government, and established a new identity for Hamas as an underdog: not terrorists, but freedom fighters. In the early 1990s, when Hamas had killed a few Israeli soldiers, but before it turned to attacks on civilians, it was a strategy that some senior Israeli officers considered a political threat.

Perhaps it could have worked. It seems, at least, a better bet than the path taken. But why did Sinwar design the operation to kill so many civilians? Part of the answer is that he didn’t. Around four in ten civilian fatalities took place at the rave at Re’im, which the operation’s planners had been unaware of. Captured documents reviewed by analysts at London’s Royal United Services Institute showed that Al-Qassam’s fighters had been instructed to assault a nearby Israel Defense Forces (IDF) command centre, but neglected their orders in order to seize hostages at the rave site.

But the remainder of the civilians killed, including all 38 children, were almost entirely at the kibbutzes. This is also where many civilians were abducted, including the children and elderly. Sinwar seems to have been surprised that the violence was not more discriminate, as required by the Islamic laws of war.

“Things went out of control,” he wrote to Hamas leaders in Qatar, claiming that the women and children among the hostages were seized by gangs, not Hamas and its allies. “People got caught up in this, and that should not have happened.” It was, at least in part, an excuse: unaffiliated individuals certainly made it out of Gaza, but not to the kibbutzes.

Doubtless, at least a significant minority of the civilian deaths were caused by IDF fire. But Sinwar should have known that a civilian hostage-taking could only end in a pool of blood. Fatah leader Salah Khalaf, who is widely believed to have overseen the 1972 Munich Olympics operation, put it this way in 1981:

Aside from the first hijacking in 1969, which caught Israel off guard, the Zionist authorities have systematically refused any compromise with the hijackers. Worse still, they have maneuvered to bring about a bloody end to each confrontation so as to set world opinion against the fedayeen. It soon became obvious that far from serving our cause, hijackings actually seriously compromised the very meaning of our struggle.[13]

Sinwar was not a naïve young militant acting spontaneously from a visceral experience of oppression. He was 60-years-old; the product of an organised national movement nearly a century old, with theoretical journals and a historical tradition.

And so he should have understood better the response that such an operation would provoke if it was successful on the planned scale. For all his vaunted fluency in Hebrew and study of Israeli society, his real understanding of his enemy was shallow. He was obsessed with its internal divisions, but had no sense of its strengths: how quickly it compacts and hardens under pressure.

He overestimated the strength and commitment of his allies. In his 2004 novel, Sinwar has a Hamas supporter reply to a Fatah supporter named Mahmoud, who says that the armed struggle is hopeless, because Israel has the strength to crush the Palestinians. The Hamas supporter replies:

Then why haven't they crushed us? The components of the equation are not merely about pure military strength, Mahmoud. Israel knows it faces an Arab and Islamic nation behind us, fragmented yes, but if it used excessive force against us, the balances of the universe would turn.

As it turned out, the universe was unmoved. Iran has saved face, while staying out of the war as much as possible. Hezbollah placed limited but real pressure on Israel; in return its entire leadership is dead, Dahieh is scarred with craters, and Lebanon’s southernmost villages are reduced to dust and ashes. From Yemen, Ansar Allah has barely made a scratch. There will be no “regional religious war.”

The most important term in the international equation was the United States, and it was here that Sinwar’s miscalculation was most disastrous. He failed to appreciate that the attacks he unleashed would allow Joe Biden, an unusually sentimental and violent backer of Israel, to let Netanyahu off the leash that had held him back in 2021. Why did he fail to recognise that?

One reason is that the lessons of Sinwar’s two major confrontations with Israel, while Gaza leader of Hamas, might have pointed in the opposite direction. The Great March of Return neither harmed nor threatened Israeli civilians; it nonetheless cost nearly 250 Palestinian lives, and failed to secure any intercession from the United States – only their veto of U.N. Security Council resolutions condemning Israel. But the May 2021 exchange of fire killed around 14 civilians in Israel, cost only a few more Palestinian lives (but several thousand fewer injured), and succeeded in engaging U.S. pressure that limited the duration of Israeli violence. The path that took Israeli civilian lives might have looked like it was more productive, and no more costly of Palestinian life and limb, than the more peaceful one.

Another reason is that the strategic proposition he had to grasp was complex. Clearly the U.S.’s professed interest in universal norms of international law and civilian protection was insincere. But it did not follow that the U.S. attitude was entirely empty. Instead, it was structured by racism. Despite U.S. disdain for Palestinian civilian life, the distinction between civilians and soldiers was still important on the Israeli side and even had some importance when it came to Palestinians.

The political criticism of Sinwar is more fundamental: that his refusal to publicly abandon his maximum political programme made any advance for the Palestinian national cause near-impossible. The Hamas position was that it wants a Palestinian state in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, but without recognising Israel or abandoning its right to fight for the remainder of the historic homeland. Under these circumstances, there was no prospect that the U.S. would pressure Israel to make fundamental concessions.

And Hamas was not able to produce sufficient, sustained pressure of its own: just a single hard, but unrepeatable, blow. Under these circumstances, any attack, even one solely focused on military targets, could achieve no more than tactical gains: perhaps the fall of the hard right coalition government, the release of some prisoners, and the bolstering of Hamas’s own domestic popularity.

Why were Hamas’s maximal goals, so clearly an impediment to its immediate ones, so hard to give up?

As David Ben Gurion confided to his diary in 1947, contemplating the partition of Palestine: “Every school child knows that there is no such thing in history as a final arrangement—not with regard to the regime, not with regard to borders, and not with regard to international agreements.” Every time Ben Gurion accepted a proposed division of Palestine, he did so only to provide the launching pad for a more ambitious project.

Why could Sinwar not adopt this attitude, and moderate his public demands accordingly?

His position was more difficult than that of the Zionist leader. Ben Gurion stood at the head of a relatively unified national movement, with big-power backing, and facing a weak and divided enemy. This combination of circumstances allowed him to make compromises while telling his base that they were a purely tactical and temporary matter. In 1937, he told the Twentieth Zionist Congress that acceptance of the Peel partition plan was “the most powerful lever for the gradual conquest of all of Palestine.” He told the Zionist Executive that “after the formation of a large army in the wake of the establishment of the state, we will abolish partition and expand to the whole of Palestine.”[14]

Sinwar did not have the freedom to manage the aspirations of his people in similar terms. Any statement by a Hamas leader is pored over for inconsistencies. Any reference to Palestinian refugees’ right of return, internationally recognised, codified in international law, and engraved in the Palestinian soul as recognition of their status as humans, will be used to paint their entire society as genocidal in its aspirations.

“One does not demand from anybody to give up his vision,” Ben Gurion wrote in his diary in 1937. “We shall accept a state in the boundaries fixed today—but the boundaries of Zionist aspirations are the concern of the Jewish people and no external factor will be able to limit them."

Today Israel and the United States insist not only that Hamas accept a political compromise, but that they give up their vision. They insist that the boundaries of Palestinian aspirations will be set from without, not from within. And perhaps that is what it has come to.

In April this year, Khalil al-Hayya, then Sinwar’s deputy, said that Hamas would lay down its arms in exchange for a Palestinian state in Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem and “the return of Palestinian refugees in accordance with the international resolutions.”

Hayya’s words were reported by Israeli media as evidence of Hamas’s intransigence, but they were strikingly close to the language of the Palestine Liberation Organisation’s (PLO’s) 1988 “historic compromise”, which opened the door to negotiations leading, notionally, to a two state solution. That document called for the settlement of the refugee question “in accordance with the relevant United Nations resolutions.”

The language opened the door to negotiations because, although the relevant U.N. resolutions currently mandate the full return of the refugees, new resolutions are always possible, and any final status agreement would likely be blessed by such a resolution. The PLO has never surrendered the right of return, but in practice discussions have revolved around token numbers of actual returnees. Hamas, battered by the war in Gaza, just as the PLO was battered by its eviction from Lebanon, seems to be on the way to a similar compromise.

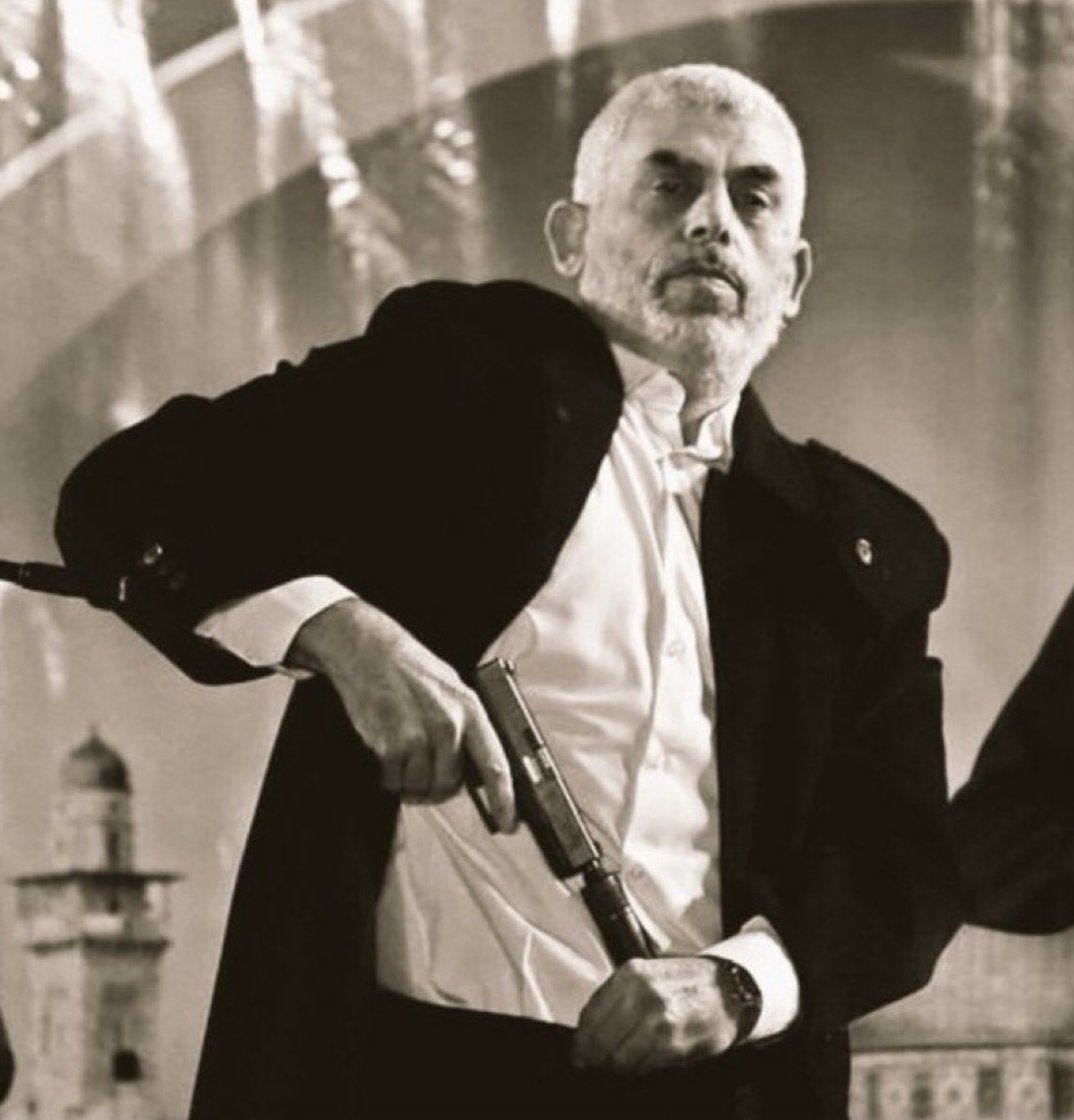

An image of victory

Perhaps, many years hence, Al-Aqsa Flood will be seen as a turning point. Perhaps U.S. pressure on Israel to grant an acceptable settlement to Palestinians will be caused by a generational shift of opinion on Israel; one brought about at the cost of the ruin of Gaza, and its tens of thousands dead. It would not be the first time such a dynamic has operated to help propel a national cause to victory. When the Algerian Front de libération nationale (FLN) bombed a bar and cafe during the Battle of Algiers – scenes depicted in the film of the same name – it provoked the French authorities to escalate a sweeping campaign of torture, one that ultimately discredited the colonial project in mainland France. That revulsion operated alongside the FLN’s military pressure, especially the killing of soldiers, and the changing tide of international opinion. Whether in Gaza or Algeria, no one who doesn’t have to pay the price themselves has any business being sanguine about it.

The FLN consciously sought to provoke general repression, albeit with the aim of turning Algerian opinion toward them, rather than eliciting sympathy in the metropole. Hamas has never articulated its own strategic doctrine in either sense; at least not explicitly, and indeed the message to its supporters that they are being offered up as sacrificial lambs to international opinion would likely be unpopular. The closest Sinwar himself came was a June 2021 speech where he promised a forthcoming operation that would “place this occupation in a state of contradiction and collision with the entire international order, isolate it in an extreme and powerful manner, and end its integration in the region and the entire world.”[15] Another Hamas leader has recently seemed enthused by the damage to Israel’s international reputation over the past year.[16]

If this dynamic turns out to overwhelm, in the long run, the destruction of Gaza, perhaps Sinwar’s reputation will be posthumously revised. But for now there is only devastation. Northern Gaza stands on the brink of ethnic cleansing, settlement, and annexation by Israel. The prospect of a permanent defeat is real.

Yahya Sinwar died as he had said he wanted: fighting Israel. When IDF soldiers ascended the stairs toward his position, on a ruined building’s second floor, he threw two grenades, seriously wounding one of them. The soldiers retreated and, according to some reports, had a tank shell the building. They then sent a quad-copter drone to scout his location. By this time, Sinwar’s right forearm was mangled, perhaps unusable. His left knee might already have been shattered open, the bone exposed; or perhaps that was yet to come. He had not eaten for three days. He must have been in terrible pain.

Yet, hunched over in an armchair, amidst the ruins, still he fought, hefting a stick at the drone, which shook in the air. After the drone left, the soldiers fired a tank shell at the building, leaving him lying amidst the rubble, but still, it seems, they did not kill him. And so when the soldiers climbed the stairs to find him, he was still alive, his ferocious determination overwhelming everything, right until the end. According to the pathologist who performed his autopsy, Yahya Sinwar was killed by a gunshot to the head.

He had always seemed to be, as a note from an interrogation 36 years earlier had described him, “one who is at peace with his words and his deeds.”

Sinwar’s failures were tremendous. They also took place in circumstances where better decisions entailed great political risks: sacrifices of his domestic position that would, in all likelihood, have gained little internationally, at least not in the short to medium term. It would have required a leader of great courage and vision to do better. Sinwar failed in circumstances that were, in part, those of Gaza, and those of Hamas, the political current to which it gave birth. But they were also circumstances shaped far from Palestine, in the capitals of the Western world. The circumstances of his failure were decided by the commitments and apathies of politicians and publics far from Gaza, for whom Palestine was never more than a marginal concern.

As Sinwar put it in his 2018 interview:

How easy it is for you to come from far away and feel wise and fair. We all have blood on our hands. You too. Where were you during these 11 years of siege? And during these 50 years of occupation? Where were you?

Thanks for reading. If you’d like to donate to help some of the many Palestinians suffering in Gaza, please consider these two fundraisers run by people I know and trust. One is for the family of Anees Mansour, who has done a huge amount to help people in Rafah himself over the years. Another, run by two friends, will supply essentials to displaced people in the Al-Mawasi area of southern Gaza.

[1] The principle exception was Betty Lahat, sometime head of prison intelligence. She reported that he was cruel but cowardly; that he cried when he learned his life was at risk from cancer. Perhaps Sinwar showed a different side to her because she was a woman, perhaps she was in touch with him at a distinct time in his life, following his cancer diagnosis, or perhaps he deliberately sought to manipulate her. An anonymous interrogator interviewed in December 2023 wrongly thought that Sinwar would do a deal “to save his skin,” but otherwise concurred with other sources. Other material in this and the subsequent sections comes from: a Maariv report on his prison grade; an FT profile; an interview with interrogator Michael Kobe; a November 2023 report on Sinwar’s confession transcript; an April interview with, and May report on, Yuval Bitton; and a New Yorker profile.

[2] An interrogator recalled: “When he spoke I thought about us, as interrogators, about all the resources we invest to understand whether we are being told the truth. That was of no interest to him at all. He tortured someone until he confessed? Yallah. Murder is permitted. He took no one into account, including the people around him. Only he decides.” Did Sinwar, part of a fledgling underground organisation, have resources to invest? Certainly not ones comparable to his Israeli interlocutors. See source in previous footnote.

[3] This was provoked by the U.S.’s attempt to crush Hamas by force when it won the 2006 legislative elections.

[4] Tamer Qarmout: “ . . . the Israeli occupation imposes crippling economic conditions on Palestinians, making the Palestinian economy dependent on foreign aid. As a result, international donors play a central role in Palestinian political life. Either because of an unwillingness to challenge Israel or because they view Hamas as a ‘terrorist’ organization, most international donors maintain their distance from Hamas. This makes it nearly impossible to achieve success in mediation efforts because any Palestinian government that includes Hamas will be automatically rejected by the international community. A key consequence of this rejection relates to donor funding, which is the main source of livelihood for Palestinians.”

[5] The square brackets indicate my adjustment of Yedioth Ahronoth’s translation.

[6] The allegation was made to Ha’aretz by a Fatah-aligned businessman who fled to Cairo last year; and may be regarded as having the status of an intriguing rumour. The businessman claimed that operatives from the Al-Qassam Brigades, Hamas’s military wing, led by Marwan Issa, had threatened polling station supervisors, forcing them to change the results in Sinwar’s favour. A contemporaneous Ha’aretz report says that Sinwar’s principle challenger Nizar Awadallah “won the first round by five votes, but needs another round to be elected to the post.” There were three other candidates; five in total, including Sinwar. A follow-up article by the same journalist says that Sinwar was elected in the second round, whereas others report that he won after a fourth round, with the first three rounds taking place in a single evening. (This indicates a form of elimination ballot that excludes candidates who fall below a certain threshold.) The contemporaneous Ha’aretz reports also offer a confused impression of the political stakes. Awadallah is described as aligned with former leader Khaled Meshal, who is seen as closer to the region’s major Sunni powers (especially Turkey and Saudi Arabia) and sometimes as more politically moderate than the faction around Sinwar, identified with Iran’s axis of resistance. But Awadallah is also described as part of “a more conservative, hawkish” faction, and less interested in reconciliation with Fatah than Sinwar.

[7] In an interview with VICE News shortly afterward, Sinwar says that Hamas informed its international interlocutors on the first day of the exchange of fire that it was willing to “willing to cease fire immediately and unconditionally,” and that his objective had been to “deliver a message to the occupation.” He also says that “if we had the capabilities to launch precision missiles, that targeted military targets, we wouldn’t have used the rockets that we did.”

[8] The origins of the concept are traced to the May 2021 conflict by, for instance, Qasim Qasir at the Institute for Palestine Studies.

[9] For example on 11, 12 and 21 May 2019, during Ramadan, Israeli forces barged into the compound and drove worshippers out at gunpoint. Sinwar declared: “. . . this conflict will only end with the removal of the occupation from all our occupied lands, and not before we return to Jerusalem and pray in the squares of the liberated and cleansed Al-Aqsa Mosque, Allah willing. We have suckled this spirit from our mothers. Our mothers breastfeed this spirit to their children along with the milk. This conflict will only end with the removal of the occupation from all our sacred soil.” It is also important that March 2019 had seen protests against Hamas’s rule over economic conditions in the enclave, and an attempted general strike, under the slogan “we want to live.” The Unity Intifada exchange of fire has a similar context.

[10] Al Jazeera on the 29 April 2022 raid; Wikipedia on the course of events more broadly.

[11] Parts of the speech with English subtitles are available here and here; it was reported at the time in various outlets.

[12] It is true that at the end of 2018 Sinwar gave a more fiery speech in which he saluted lone wolf attacks in the West Bank; but he did not refer to such attacks in Israel. An Israeli special forces unit had been identified, attacked and repelled during an undercover incursion into Gaza. Sinwar was presented with the pistol of a killed IDF commando.

[13] Abu Iyad with Eric Rouleau (1981) My Home, My Land: A Narrative of Palestinian Struggle, p105

[14] During the 1930s, he even felt free enough to tell even Arab leaders that he envisioned a Jewish state extending, in Simha Flapan’s summary, “from the Mediterranean in the west to the Syrian desert in the east, from Tyre and the Litani River to Wadi Ouja (twenty kilometers from Damascus) in the north to El-Arish in the Sinai Peninsula.”

[15] Video of speech via Al Araby, translation of passage via Hanna al-Shaikh at the Arab Center D.C. Unfortunately for Palestinians, Sinwar’s promise proved excessive: Israel remains broadly integrated into the world system. But even as an interrogee, Sinwar had sought to goad his enemy, to draw him into an overreaction. One interrogator remarked that Sinwar was unusually adept at making him “liable to lose control and do things that must not be done and get into trouble.” As a result, the interrogator felt the need to leave the room frequently. In his speech at the Revonia Trial, Nelson Mandela did say that one of Umkhonto wa Sizwe’s strategic motivations for its campaign of sabotage was that if the authorites took “mass reprisals” taken, we felt that sympathy for our cause would be roused in other countries, and that greater pressure would be brought to bear on the South African Government.”

[16] See comments of Basem Naim to the New Yorker’s David Remnick.

In this piece, I raised the possibility (not the certainty) that the long-term effect of Israel's war in Gaza would be to isolate it. It appears Biden's ambassador to Israel is worried about exactly the same dynamic:

“. . . what I’ve told people here that they have to worry about when this war is over is that the generational memory doesn’t go back to the founding of the state or the Six Day War, or the Yom Kippur War, or to the intifada even. It starts with this war, and you can’t ignore the impact of this war on future policymakers — not the people making the decisions today, but the people who are 25, 35, 45 today and who will be the leaders for the next 30 years, 40 years.”

https://www.timesofisrael.com/the-ambassadors-farewell-warning-you-cant-ignore-the-impact-of-this-war-on-future-us-policymakers/

You are missing the bigger picture. Palestinians and Yahya Sinwar has given rise to a global anti imperialist movement.