Why did Assad fall so fast?

The geopolitics of U.S. power, and the Syrian politics of revolution

The Assad dynasty had stood for 53 years at the head of Syria, including a dozen years of war. In December, it collapsed after a rebel offensive lasting just a dozen days.

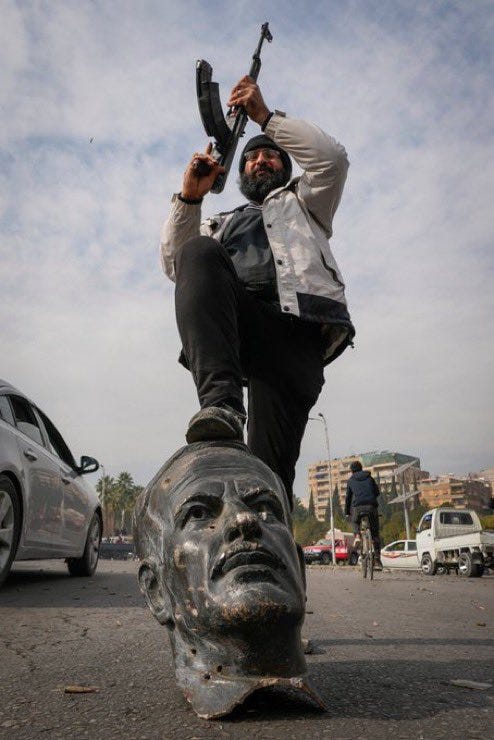

The speed of it shocked everyone. It shocked even the rebels, who had named their operation Deterrence of Aggression, as if it was just one more manoeuvre in a war whose end had become almost inconceivable. In days, they took Hama, the site of a notorious massacre by President Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez, in 1982, that had intimidated a generation of Syrians into quiescence. Who was to know that the twelfth attempt to take that city in as many years would be the one that would, at last, spell the end of his dynasty?

This brittleness had observers scrambling for explanations, and for some, there was one ready-made, to hand.

“This isn’t about dictators or democracy, it never was,” wrote the commentator Rania Khalek. “It’s about U.S. Empire trying to strangle a crucial supply route for resistance to it.” It was apparently a widespread sentiment. In this view, Syrians’ struggle over the shape of their own future was a mere footnote in a bigger and more important story: a geopolitical battle between the U.S. and its enemies over the supply line running from Iran to Hezbollah.

And so Syrians are reduced to bit-part players in their own story.

It is true that U.S. power played a role in Assad’s collapse, but it was one part of a bigger whole, which included both domestic and international dynamics. In the end, the U.S. might not have been the most important international actor. And the specific character of the Assad regime – unusually cruel, vindictive and venal, even by the standard of autocracies – was at least as important in its own demise.

Turkey, refugees, and why rebel Idlib survived

If one fact, more than any other, lead to the downfall of the regime, it was that a huge proportion of Syrians considered Assad’s rule so dangerous and terrifying that they preferred to become refugees than live under it.

Between 2011 and the end of 2019, about 3.5 million Syrians had fled to Türkiye. There, the 2019 local elections delivered a surprise setback to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP). While it’s not clear that antipathy toward Syrian refugees explained the AKP’s loss, Erdoğan’s response left no doubt that he saw it in those terms.[1]

By February 2020, Assad’s forces, backed by Russian aviation, had been on the offensive in Idlib for ten months. They had conquered about half the enclave. Not only did three million Syrians live in the pocket that remained, but many had already been internally displaced, having fled from Assad one or more times already. Idlib had become a dumping ground for the irreconcilables; a concentration of those who had fought Assad, and agreed to leave for Idlib rather than struggle to the bitter end in the various parts of Western Syria where they had taken up arms.[2]

It therefore stood to reason that they would flee again, and there would be nowhere to go but Türkiye. This, Erdoğan could not accept. With the spark provided by a Russian strike on a Turkish army convoy in Idlib, Erdoğan initiated a direct attack on the Syrian Arab Army (SAA).[3] Putin recognised that Russia was not prepared for a conflict on Türkiye’s southern border, and stood aside. Without an answer to Turkish airpower, the SAA took a heavy, one-sided beating.

The fighting was ended by an accord that, whatever its formal terms, established that Russia would not support an offensive to take Idlib, and that Türkiye would resist one. It was not really a ceasefire. For the next four years, Assad’s forces continued to bomb Idlib. But everyone understood that if Assad wanted to retake Idlib entire, he’d need to do it without Russia, and in the teeth of Turkish firepower.

There’s no evidence that Turkey provided positive support to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the leading rebel organisation, whose leader Ahmed al-Sharaa – formerly known by his nom de guerre, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani – is now the head of the transitional government in Damascus. HTS was still designated a terrorist organisation in Türkiye. But Idlib’s northern border remained open in a way that Gaza’s border with Egypt, for example, has not been since 1967. Türkiye also provides support to some factions allied with HTS.

Ankara reportedly knew about the planned offensive six months in advance, and gave its tacit approval. Erdoğan wanted Assad to compromise with the more “legitimate” elements of the opposition, in order to resolve the war in a manner that would allow the refugees to return home, and invited Assad to Ankara several times to discuss the prospect. But the Syrian premier refused. He understood that the opposition would insist that he step down, and he would not accept the loss of his patrimony. It was not Syria, in the end, that he wanted to defend, but his dynasty.

Protection from an existential assault gave Idlib’s rebels the opportunity to build a state and economy which – for all their manifold faults, including some serious rights abuses – offered most Syrians a more appealing image of the future than that visible in Damascus. The advance was most obvious in the field of the protection of minorities. For most of their time in charge of Idlib, Islamists persecuted Christian and Druze minorities, often by appropriating their property. But in September 2023, perhaps partly in an effort to get terrorism designations lifted, the administration there begun systematically handing property back, and invited Christians and Druze who had fled to return.

The rebels adopted the Turkish lira and plugged in to the Turkish internet, tightening Idlib’s connection to the unsanctioned Turkish economy. They also reformed their military, complete with its own officer training college, and a drone programme, replete with 3D printers and simulator games. That programme had some “modest” help from Ukraine.

All this was possible only because Assad’s victory in one more province of Syria, and in particular one on Türkiye’s southern border, was incompatible with Turkish interests. That, in turn, was because so many Syrians were unwilling to live under Assad.

That’s hardly surprising. Former refugees who returned to Syria were “raped, tortured, disappeared,” according to Amnesty International, suffered “gross human rights violations and abuses” according to the UN Human Rights Office, and “enforced disappearance, torture, and death in detention” according to Human Rights Watch. At least 208 refugees deported from Lebanon were arrested in Syria during the first ten months of 2024, of whom at least six were subsequently tortured to death.

Some, no doubt, were held in the notorious Sednaya Prison, just outside Damascus. When Rania Khalek visited Syria in 2019, hosted by regime supporters, she posted a scenic photograph overlooking Sednaya at dusk. “Breathtaking view,” she wrote. The prison was just out of shot: an apt illustration of Khalek’s unwillingness to acknowledge what went on inside.

A hollow shell

Assad fell not only because the Idlib rebels had the opportunity to build their state and prepare their offensive, but because the regime itself had become hollowed out from the inside. Much like the rebels’ survival, this hollowing-out was the result of both external forces and Assad’s own venality.

Assad projected an image of uncompromising strength. After retaking most opposition-held areas of the country after 2016, he presented himself as both victor and great survivor. And yet, beneath, there lay endemic, stifling corruption, poverty, Syria’s emergence as a narco-state, and the persistent violence of the security services, who offered security to none but themselves. Assad’s supporters found that the spoils of their victory were nothing but unending hardship and humiliation.

With the benefit of hindsight there were signs of regime deterioration everywhere: a sustained protest movement in Druze-majority Suwayda and rumbles of mounting dissent elsewhere; regime insiders increasingly willing to curse Assad and his inner circle, if only in private; destitution almost everywhere, with no end in sight.

The economic stagnation was undoubtedly exacerbated by Western sanctions. When the U.S. first sanctioned Syria in 2004, it was in response to Syria’s support for Hezbollah, its support for militants attacking U.S. forces in Iraq, its occupation of part of Lebanon (until 2005), and its chemical weapons programme. Whether or not those amount to “resistance” to the “U.S. Empire,” the reality is that those sanctions were irksome, but a shadow of the current programme. By 2022, public electricity was limited to three to six hours per day in most of Assad-held territory, limiting the operation of industry and the provision of clean drinking water. Lacking fertiliser, food production had plummeted. Sanctions hurt opposition areas too, albeit less fiercely than regime-held ones.[4]

The more stringent sanctions imposed in 2011, and escalated in 2020, were prompted by Assad’s repression of the uprising, and by disgust in the wake of the Caesar images, which depicted the regime’s treatment of detainees. By that time, Syria was no longer backing attacks on U.S. troops, was no longer occupying Lebanon, and while it retained some chemical weapons, its stockpiles were much reduced. The intensity of sanctions increased long after Syria’s “resistance” fell to its lowest ebb. By the time of his fall, Assad still permitted Hezbollah to bring weapons through Lebanon, but gave them no protection from Israeli strikes, and in July 2023 seems to have barred them from using the Hmeimim air-base. There had been discussions, led by the UAE and Saudi Arabia, of exchanging sanctions relief for a Syrian break with Iran, but it’s not even clear that the U.S. was itself willing to put the sanctions on the table.

According to Assad himself, who may have been trying to deflect from his own responsibility for the sanctions, the 2019 banking crisis in Lebanon was the main cause of Syria’s economic woes. He claimed that Syria had lost access to a sum of between $20 billion and $42 billion, a staggering sum – between five and ten years’ government expenditure at the levels projected for 2025.

The regime’s loss of the oil fields in eastern Syria mattered too.[5] But according to a 2024 Oxfam-published study, “even in the event of increased fuel availability, 35% of power generation capacity would still not be available due to technical factors.” Those included brain drain – the decision of many qualified Syrians to flee Assad-controlled areas. And fuel scarcity was not only caused by the division of the country, but regime policies, “corruption and war economy dynamics.” For years the Assad dynasty had granted de facto economic monopolies to their supporters, and state officials had always taken bribes as a means to make up for their poor wages.

The institutions of the Syrian state had been weak before 2011 – every other function subordinated to their role as props for Assad’s rule. During the war, their weakness and their servility intensified. That included the army.

But, nonetheless, in February 2020, the SAA held off an eight-day assault on their positions in Idlib by rebels, who were backed by Turkish airstrikes. Assad’s troops on that front got little backing from Russia, Iran or Hezbollah, and none from the Syrian Airforce. They lost some 400 men, but held their ground. What changed in the subsequent four years? Why did morale collapse so severely that tanks fled from a charge of lightly-armed men in pickup trucks?

Analyst Gregory Waters, a close observer of the Syrian military, draws attention to several factors. Promotion had long taken place on the grounds of loyalty rather than competence. Officers had been withdrawn from frontline roles in order to reduce their death rate; an approach which worked, but reduced the quality of leadership in combat. The standing army and the reserves were both shrunk in size, probably to cut costs, which took many veteran officers away from the front lines. The army, much like the rest of the state bureaucracy, seemed to many of its soldiers like a vehicle for organised crime rather than defence of the nation.

Over five months, according to soldiers, officers in the 30th Division took bribes to exempt their subordinates from service, stole food and fuel allowances, abused their troops in sectarian terms, extorted both soldiers and civilians, looted antiquities and agricultural produce, ran a smuggling operation to the rebels, and got drunk on duty. One allegedly entertained sex workers in his office near the front line. The SAA was so weak at the beginning of the war that it needed to be rescued by Russia and Iran. But by 2020 it had evidently gained some experience and esprit de corps, at least on the Idlib front. By 2024, it had reverted to type: a mechanism for graft.

The rot was visible in accounts from combatants on the SAA side. One SAA officer described having to retreat at the rebels’ first assault in November because his men lacked ammunition and were badly outnumbered, despite that the prospect of a rebel offensive was well-known. His men then defended a fall-back position without food or water for two days, before being hit by a wave of rebel suicide drones. “Our commanding officers vanished, leaving us to fend for ourselves,” the officer said. After carrying a wounded soldier to the hospital, he left to his home village.

A hollow man

The rebels had used the intervening years to reform themselves, to establish standards of governance, leadership and discipline, to moderate their politics, and to increase their internal cohesion. They did so despite being subject to sporadic bombardment, the secondary effects of sanctions, and a terrorism designation. There is little sign that Assad even attempted anything similar: every potential reform, every possible concession, he saw as nothing but an invitation to weakness. He sought to eradicate divisions within his society through violence, rather than bridge them through politics. He adopted his father’s posture of intransigence, but without either the strength or the political wiles to back it up.

Once the country started slipping from his hands, it became clear that not only had Assad lost the army, he’d lost the population—including his traditional loyalist base. And his erstwhile allies were absent without leave.

Russia was overstretched in Ukraine. It had taken to using Syria as a dumping ground for officers considered incompetent. But it held fast to its intention to support Assad right until the last. As late as 4 and 5 December, Russia was declaring solidarity with Assad, and gave every impression that they wanted to beat back the “terrorists.” But the offensive was moving too fast for the reduced complement of Russian aviation still stationed in Syria to cope. Ultimately, the Russian effort to support Assad ended in the manner that it had begun: bombing hospitals; perhaps in a hopeless, last ditch effort to cause a refugee crisis that would cause Türkiye to change its calculus.

Over a dozen years of war, Iran strove to save Assad and, with him, its land bridge to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) officers integrated themselves into the regime’s military and security apparatus, and in the early years of the war helped form several of the militias that allowed Assad to survive. But after more than a year of punishing Israeli airstrikes against IRGC and Hezbollah operatives in Syria and Lebanon, neither party had the resources on hand to respond to Assad’s lightning collapse.[6]

The fall of Homs was a telling moment: the city was an essential conduit for Iranian weapons shipments moving from the Syrian-Iraqi border, via the central Badia desert, towards the Syrian-Lebanese border in south-west Homs. But in the preceding days, Israel had struck border crossings used by Hezbollah, and a Hezbollah convoy heading back toward Lebanon. Even if the group felt able to send reinforcements, they must have doubted whether those would have reached the strategic city intact.[7]

A Syrian revolution in an internationalised war

If the U.S. had really wanted Assad gone, Assad would have gone long ago. It look Israel just a few nights of airstrikes to destroy the Syrian Army. It would never had been more difficult for the United States.

U.S. support for Syria’s armed opposition between mid-2013 and mid-2017 was intended to cohere a secular opposition current, marginalise the jihadists, and place pressure on Assad to arrive at a “negotiated settlement that leaves Syrian institutions intact.”[8] In these objectives, it was a failure. By 2015, when Assad appeared to be on the brink of defeat, the U.S. concluded that it would be “catastrophic” for the rebels, fractured and dominated by jihadists, to win. They “worried that the Assad Regime might finally collapse – and do so quickly, in a way that would endanger U.S. interests, to include the security of the state of Israel.” Like Rania Khalek and her co-thinkers, U.S. strategists ultimately decided that whatever his flaws, given the character of the opposition, it was better for Assad to stay.

The timing of the rebel’s November 2024 offensive was indeed “no coincidence.” From late September onwards the Idlib rebels were busy moving around troops and bolstering their front-lines at different points – some of which were likely feints to misdirect the regime. After weeks, then months, without an offensive, the 27 November Israel-Lebanon ceasefire suggested that the time was right. Hezbollah, which had fought on Assad’s side since 2012, was weaker than ever.

At that moment, as at every other, international dynamics shaped the political space in which Syrians contested their future. But that space left a lot of room for manoeuvre and, within in, it Syrians decided, acted, dared, and shaped their future. Assad’s decisions were decisive: to choose his dynasty over his country, and to rule by violence, torture and displacement over inclusion, dialogue and democracy. The rebels innovated and exploited the slight opportunities they were given, not on behalf of U.S. or Israeli interests, but on behalf of their own. Syrians as a whole voted with their feet: too many preferred to live outside Assad’s rule to give his regime the stability it needed.

Some outside observers, including Rania Khalek, see the world through an archaic lens derived from the struggle against the European colonial empires, and not revised since.[9] They imagine, usually in error, that a motley series of dictators and non-state armed groups have the capability and desire to realise emancipatory goals, such as the liberation of Palestine. From there, some combination of moral and intellectual rot sets in. They have to be willing to accept the gulags and massacres of their favourite dictator as the necessary price of their project, or they have to be willing to pretend that they don’t exist. Or both.

For these people, Syrians and their agency scarcely comes into it. As the Syrian intellectual and former political prisoner Yassin Haj al-Saleh put it:

They are interested in high-politics, not grassroots struggles. They are dealing with grand ideologies and historical narratives, but they don’t see people—the Syrian people aren’t represented. They are holding on to depopulated discourses that don’t represent human struggle, life, and death.

The genocide in Gaza continues, and the situation for many families trapped there is desperate. If you’re looking for a way to donate to Palestinians in need , the authors of this post can recommend a couple of options. To support people in Al-Mawasi, where babies have been dying of cold, please support this fundraiser for the family of Tom Dale’s friend Anees or this project coordinated by other friends of his, Kareem and Ellie, which provides food to families in need. Tom Rollins recommends Grassroots Gaza.

[1] On one account, “the government responded [to the 2019 election setback] with further restrictive policies, such as removing unregistered Syrians from Istanbul.” And, “starting with 2019, we can observe the rise and success of extreme-right political actors focusing on anti-immigrant/refugee sentiments. This was later followed by the formation of the single-issue and anti-immigrant Victory Party (ZP) under the leadership of Ümit Özdağ in 2021.” The 2020 Operation Peace Spring intervention, and its origins in the Syrian refugee issue, is covered by, for instance, Gönül Tol in Erdoğan’s War (2022), pp270-285. Even earlier, in 2018, Erdoğan had secured an agreement from Assad’s ally, Russian President Vladimir Putin, to preserve the Idlib enclave, the last remaining redoubt of the armed rebellion in West Syria, for the same reason. But the agreement reportedly had a number of implausible stipulations, including that Hayat Tahrir al-Sham would have to leave the enclave.

[2] This was not a mere side-effect of Assad’s approach. According to Emile Hokayem, speaking in 2020, Assad’s “strategy from [the] outset has been one of de-population.” Kheder Khaddour and Armenak Tokmajyan expanded on this point in 2024: “In 2016–2018, some 200,000 Syrians living in opposition areas recaptured by government forces agreed to be transferred to northwest Syria, notably Idlib Governorate. They preferred this to finding themselves at the mercy of the Syrian government and its security forces. The regime accepted this option as a way of addressing the predicament it faced of what to do with a large and antagonistic population. The regime’s move, facilitated by Russia, meant accepting the loss of control over part of its population, effectively ceding a key component of its sovereignty. Presumably, this was a temporary measure, with the intention of recapturing the northwest at a later stage in the conflict.”

[3] Erdoğan knew that Russia carried out the strike but chose to blame the SAA in order to legitimate his intervention.

[4] See here, summary of references in the paragraph beginning “Sanctions have blocked rehabilitative services in areas not controlled by the regime.”

[5] A variable proportion of the oil produced in Eastern Syria was sold to the Assad regime, both under the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), for whom at times it was the major source of revenue, and the current Syrian Democratic Forces administration.

[6] According to some reports, Assad had also come under pressure from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to reduce the Iranian footprint in Syria.

[7] Some analysts have emphasised a growing rift between Assad and Tehran, citing the recent closure of the Houthi office in Damascus, Assad’s refusal to allow a Golan front to be opened against Israel, and an apparent decision in July 2023 to pause or halt weapons shipments to Hezbollah through Russia’s Hmeimim air base. But in reality Syria’s relationship was never founded on close ideological sympathy: it was a shallow alliance of convenience. The more compelling evidence indicates that, in the event, Iran was simply unable to help. A senior Middle East diplomat told Amwaj “that despite the Syrian government’s urgent request for Iranian support, logistical constraints and operational risks—including potential Israeli airstrikes—made such assistance impractical.”

[8] Arab states and Turkey, as well as private actors in those states, begun funnelling military support to a mosaic of rebel factions in Spring 2012 and by May 2012, U.S. personnel were coordinating some of that assistance. This U.S. effort was an attempt to prevent arms ending up in jihadist hands, and forestall the fracturing of the opposition, both of which failed. By March 2013, Americans (likely private contractors hired by the Jordanian government) were training Syrian rebels in Jordan, with a focus on anti-tank weaponry. The decision to provide direct lethal assistance, under the code-name Timber Sycamore, was made in late April 2013 and announced in June of that year. President Obama had agreed to the programme only reluctantly, and remained sceptical of it throughout his tenure. However, at lower levels of the administration there was “satisfaction”, even “excitement” at the rebel gains the programme produced (Joby Warrick, Red Line (2020), Chapter 17). From mid-2015, the focus of the programme had ever-more to do with preventing jihadist dominance over the opposition and ever-less to do with directly fighting Assad. In February 2017, rebels in the North-West who had been receiving support under the programme were told that they would receive no more arms or ammunition unless they united to “to form a coherent front against the jihadists.” In June 2017, President Donald Trump cancelled the programme, which had cost around $1 billion.

[9] The following passage from Sinthujan Varatharajah and Moshtari Hilal’s recently published book, Hierarchien der Solidarität [Hierarchies of Solidarity] (2024) goes some way to explaining this: “Most people in Europe and in the European settler colonies understand power relations—especially colonial and imperial violence—solely through Europe and European bodies. But Europeans don't actually have that monopoly. As soon as these forms of violence come from non-Europeans, directed at other non-Europeans, they can no longer be understood by them as colonial or imperial.”